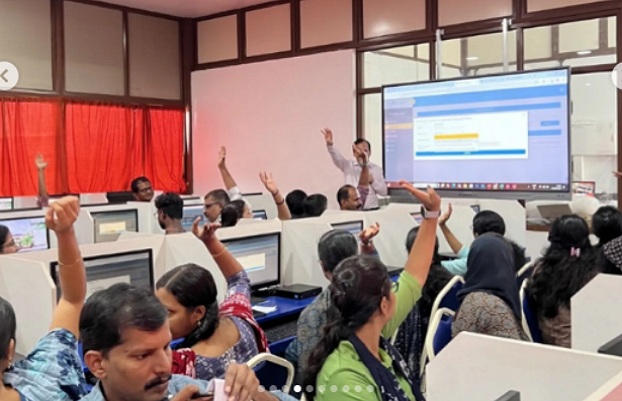

ipsr solutions limited, an award-winning EdTech company in India, was founded in 2000 by visionary academics and dynamic entrepreneurs. Thanks to its pioneering academic solutions, value-driven IT services and highly acclaimed global IT certification training, it has earned a reputation as a company dedicated to developing innovative, sustainable, and transformative IT solutions and services.

Read more about usAI-assisted academic platform that generates question papers, course outcomes, syllabi, or assignment topics within minutes by simply entering the syllabus or topic.

Want to learn more?A cost-efficient, secure Question Bank Management Platform with instant question paper generation, designed for colleges and universities, focusing on OBE, quality control, and best practices.

Want to learn more?An innovative tool that aids HEIs in managing Outcome Based Education comprehensively, from defining POs, PSOs, and COs to calculating attainment and generating reports for accreditation agencies.

Want to learn more?deQ Learning tailors Moodle LMS to HEI needs with expert consultancy, fostering efficient, engaging, and results-oriented learning environments.

Want to learn more?An innovative platfrom aiding Higher Education Institutions in quality monitoring and maintenance based on diverse criteria for accreditation. Helps teachers in generating PBAS/CAS and API reports.

Want to learn more?deQ: AMA, a comprehensive suite of applications designed to streamline academic, administrative, and financial operations for academic institutions.

Want to learn more?

Number Speaks

Skill up your life

IT Services

We deliver reliable, end-to-end IT services tailored to your needs. Our experts will work with you to design and build custom web and mobile applications, content management systems, e-commerce platforms and business software to power your business in the age of AI.

Go toExperience tailor-made web solutions crafted by our experts. Customised to fit your unique needs, driving your digital success.

Maximise your mobile potential with our bespoke app development services; crafted solutions for immersive user experiences, and accelerated business expansion.

Experience seamless content management with our CMS development services, custom solutions for efficient organisation, and easy website maintenance.

Elevate your online store affordably with our e-commerce solutions, designed to amplify your online presence and drive sales seamlessly.

Discover eZcom: our' streamlined accounting software that integrates GST features. Choose from five versions tailored to your needs.

Boost your online presence with our Digital Marketing services; tailored strategies to enhance visibility and drive growth effectively.

Learning Services

Latest Updates

Upcoming Event at Kerala University of Fisheries and Ocean Studies […]